When the English initiated the plantation of Ireland in the mid to late 1500s, Ulster – in particular East Antrim and North Down – was among the first places to see English colonisation. In 1573 Walter Devereux, the 1st Earl of Essex landed in Carrickfergus to conquer the province in the name of Queen Elizabeth I. Although the full extent of his plans never came to fruition, he brought with him an army of around 1,200 men. One of the officers who travelled with Essex was John Dalway (1550-1618). His rank at this time is unclear – records describe him as a Captain beyond 1600, but he may have a arrived a Lieutenant. Dalway would become an extremely important figure in the history of the town, and indeed much of east Antrim, at the head of a vast cattle empire spanning all the way to lowland Scotland, via the “Cassie” cattle trail in Carrickfergus.

Background

In 1571, Elizabeth I granted 360,000 acres of Clandeboye Ó Néill lands in north Down and south Antrim to one of her most trusted Privy Councillors Sir Thomas Smith, and he sent a small company of soldiers to Strangford sometime thereafter to claim them. Sir Brian mac Felim Ó Néill held the lands at this time. He had himself been knighted by Elizabeth, and reacted with fury at this betrayal, destroying and scorching the lands to prevent any colonisation attempt. This, along with the fact that Smith brought only 100 men with him, meant that the venture was short-lived. It was these lands that Essex hoped to colonise, this time successfully.

When the English arrived, the lands surrounding Carrickfergus were still held by Brian mac Felim. They surrounded the town on all sides, and the county and town of Carrickfergus was under a “black rent”, where money was paid to the Clandeboye Irish in return for Carrick’s international sea trade remaining intact. Brian mac Felim quickly moved to wage war on the English, after Essex unwittingly revealed his plans to use the Irish to destroy the Scots in the north.

In 1574, Brian mac Felim invited Essex and his men to a feast near Belfast. After the feast, intended by the Ó Néills as a gesture of goodwill, Essex treacherously slaughtered 200 of Brian mac Felim’s men and arrested him, taking him to Dublin to be executed. Essex took some 3,000 cattle from Brian mac Felim and claimed that they had been stolen from the commons of Carrickfergus.

The lands east of Carrickfergus passed to his son Shane mac Brian Ó Néill, who was now forced to place greater importance in moving valuable cattle to Larne, Portmuck and Whitehead without passing through land dominated by Essex between Belfast and Carrickfergus. What was born out of this need was the expansion of a number of cattle-droving trails, the main one of which travelled from Ballynure, east towards the main three ports, and passed through the commons of Carrickfergus north of the town.

Dalway

By the time Essex had died in 1597, John Dalway had settled in a tower house in High Street in the town and soon married Jane mac Brian Ó Néill, a daughter of one of the chiefs of the Irish Clandeboye clan – some sources name Hugh Ó Néill, the Earl of Tyrone. They had an only child in her early twenties, Margaret Dalway (born c1575). In 1591, he was granted lands in Kilroot parish and Broadisland [Ballycarry] by his wife’s close relative Shane mac Brian Ó Néill. These lands were on the eastern side of the Copeland Water, which denoted the boundary of the town of Carrickfergus. The western side, known as Marshallstown, had been entirely English territory since the Anglo-Normans invaded Ulster and was usually held by the Marshall of the town and county, an office first held by Sir Roger de Copeland.

Tensions between the English and the Scots had reached breaking point at this time. By 1597 the Scots had encroached onto Dalway’s lands, and soon arrived at the North Gate of the town in a show of defiance. English governor John Chichester gave chase to the Scots with a small force of horsemen, including John Dalway and John Dobbs in their military roles, but they were ambushed by a much larger Scottish force near Ballycarry in an area known as Aldfracken Glen. After the Battle of Pin Well (in which Chichester lost his head) Dalway, who had escaped by hiding in the low-tide mud and silt between Islandmagee and the mainland, was forced to flee his now highly contested (and dangerous) lands.

The turmoil between the English and the Scots died down around 1603, with the surrender of Hugh Ó Néill and the death of Queen Elizabeth. In the same year, Dalway’s daughter Margaret married John Dobbs, a young English officer who had arrived in 1596 with Sir Henry Dockwra. Dalway gifted the newly-weds a portion of the Dalway lands as a freehold lease, which would become known as Dobbsland.

James I of England and Scotland now sat on the throne, and in 1608 he issued John Dalway a re-grant of “such lands as he held in right of his contract with Shane Ó Néill”, and so Dalway returned to his lands. One of the many conditions of this grant of land was that Dalway was to build “within the next seven years, a castle or house of stone or brick … with a strong court or bawne about the same, in any convenient place, within the territory of Ballinowre [Ballynure]”.

“Bawne” or “Bawn” is thought to be a corruption of the Gaelic word bábhún (or “bo-dun”), meaning a cow fort or walled cattle enclosure. These bawns were fortified “cattle forts”, designed to be a place of sanctuary from cattle-raids carried out by the Irish along the many cattle-droving trails in east Antrim at the time. They typically have thick walls, four corner towers for defensive look-outs and a house in the middle. Dalways Bawn would become one of many such bawns built during the Plantation of Ulster.

Despite the king’s grant, Dalway still had to be cautious about external claims to his lands at this time. In the early 1600s Englishman Baptist Jones held large swathes of land in Marshallstown as a tenant of Sir Arthur Chichester, but also lay claim to several hundred acres of Dalway’s land “across the mearing” in Kilroot Parish, which may have extended to the bawn. This claim leaves its mark in modern day as the tiny townland of Crossmary. This threat to Dalway’s land seems to have come to nothing. Jones took over lease of lands belonging to the Worshipful Company of Vintners in Bellaghy in 1617 and is likely to have relocated there at this time. He established his own bawn there (Bellaghy Bawn) in about 1619. He later became head of the company and was knighted in 1621.

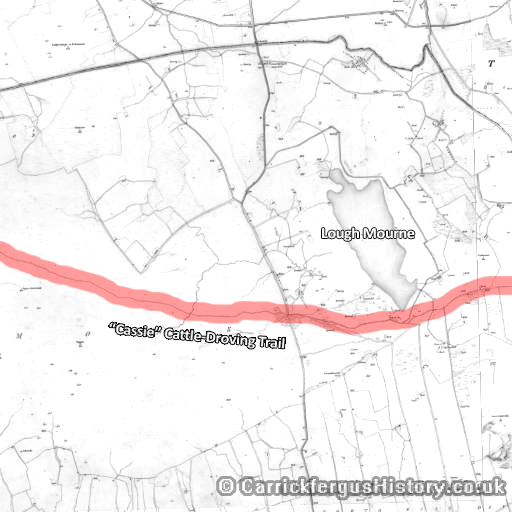

Dalway would construct two bawns, intended to add protection to one of the busiest and most profitable cattle-droving trails, which crossed Dalway’s land – The “Cassie”. The Cassie cattle trail began in Ballynure, where cattle, horses and pigs would be shown and sold at the Fair Hill. It then passed Castletown Bawn nearby and then down through the Commons of Carrickfergus past Dalway’s Bawn. They would then be driven down the trail towards either Whitehead or Portmuck (“muc” from the Gaelic for pig), where they would be loaded onto ships and continue their journey to similar droving trails in Scotland, including what would become the Galloway cattle-droving trail.

Dalway was still free to sub-let or sell the land to any English or Scottish person as he saw fit, and without the king’s direct consent. John Dobbs and his new wife Margaret moved onto the lands that Dobbs had now married into, and in 1599 built a grand house known as Dobbs Castle or Castle Dobbs. There they had two sons, starting a line of Dobbs men who would become incredibly important in Carrickfergus, and later in the Thirteen Colonies in North America.

Dalways Bawn

Dalways Bawn is a cattle-fort situated in the southern part of Bellahill townland, close to Dobbsland. It was built in about 1609 according to James I’s 1608 re-grant of land to John Dalway in order to protect the Cassie cattle-droving trail from Irish cattle-raiders. Per the traditional design, the bawn had four corner towers approximately 30ft high, connected by a curtain wall about 25ft high, which itself spanned approximately 133ft between the towers.

The centre of the bawn would have featured a dwelling in which the landlord of the fort would live. Around this dwelling was enough space to house some 200 head of cattle at any one time, and slightly more should there be an urgent need. Above the entrance of the bawn is an iron ring, which most sources note as once having housed a primitive gallows for unwelcome visitors.

In modern day, the bawn is immediately adjacent to Dalways Bawn Road, which itself runs from Ballycarry down to the main coastal Larne Road. Across the road, only one or two modern fields separate the bawn from the more wooded setting of Dobbsland, legacy of the Dobbs family. Three of the four towers are still standing, the south-western tower having disappeared and the remaining three having been carefully restored by the state. Only two are visible from the road. The central dwelling is long gone, and modern farm buildings occupy the middle of the bawn and the area to the north, the northern curtain wall having disappeared. Careful inspection of the front curtain wall reveals that there were previously large arched openings, designed for small cannon. These have been filled in and replaced with much smaller openings modified for rifle-fire.

The bawn was made somewhat redundant for its original purpose, when the commons (through which the cattle trail ran) were enclosed in 1860 and the land divided up and made available for sale or lease. The last of the Dalways to live at the bawn – Marriot Robert Dalway and his family – emigrated to Australia in 1886, settling in Lorne, Victoria. The bawn is still very much in use as farm buildings today, but is a recognised archaeological site of historical significance.

The Cassie

The Cassie is the name of possibly the busiest former cattle-droving trail in east Antrim. The name comes from the Scots (and subsequently Ulster Scots) for “causeway”. The term, along with its alternatives “causey” and “cassay”, were later used in reference to cobblestone roads.

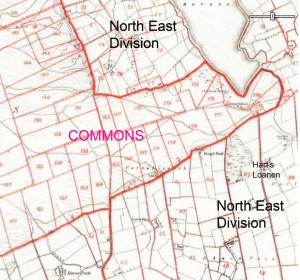

The Cassie started at (or close to) Ballynure’s Fair Hill, where cattle, pigs and horses were brought for show, and eventually sale. The location of the Fair Hill is unclear, as is the location of Castletown Bawn, another of Dalway’s cattle forts just outside Ballynure. It meandered through the hills to the south-east, and through the uninhabited commons of Carrickfergus, where it passed the source of the Woodburn River, named on 19th century maps as “Bryan O’Neill’s Well” after the Gaelic chief who had such an impact on the area years before. Further south of the trail, small cabins and shanties began to appear over the course of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, skirting the boundary of the commons, on which it was prohibited to build dwellings – peat diggers, drovers and illegal farmers and hunters who wanted to take advantage of the wild commons.

At the southern end of Lough Mourne, the Cassie is connected to Boneybefore by Harts Loanen, sometimes known nowadays as Downshire Lane. It’s not clear when Harts Loanen appeared, but it was certainly in existence by the late 1700s to early 1800s. Today the lane crosses the Marshallstown Road to the south and ends at Prince Andrew Way, and the lower portion near Boneybefore is now Downshire Road.

While in the commons, the cattle and their drovers had the benefit of travelling within the county of Carrickfergus, a fairly solid deterrent to Irish attack. Once the trail passed the Copeland Water just east of Lough Mourne the drovers were in more exposed lands, claimed by both the Irish and Scots at one point or another, and vulnerable to attack.

Dalways Bawn was situated as a refuge just outside the boundaries of Carrickfergus, and possibly the only one before the final destinations of Whitehead, Portmuck or Larne.

From about 1608 onwards, a multitude of tenants and sub-tenants lived and farmed on Dalway and Dobbs land east of the Copeland, and the Cassie naturally became an essential thoroughfare, providing access to many farms and homesteads. Through the 1700s and 1800s, farming families such as the Hartes, Esslers, Hoeys and Jacksons kept farms in Bellahill, with driveways and lanes accessible from the Cassie. Some notable residents were Andrew and Elizabeth Jackson, parents of future US President Andrew Jackson, whose family farm was located up a lane accessible from the Cassie.

In the 1800s, hawthorn hedgerows were planted along either side of most of the trail, narrowing the trail but providing better containment for the cattle, preventing them from straying. The death knell for the Cassie came in 1860, when the commons were enclosed and cleared for habitation. The land was divided up into fields ready for farming, which would almost entirely bury the trail cutting through the area.

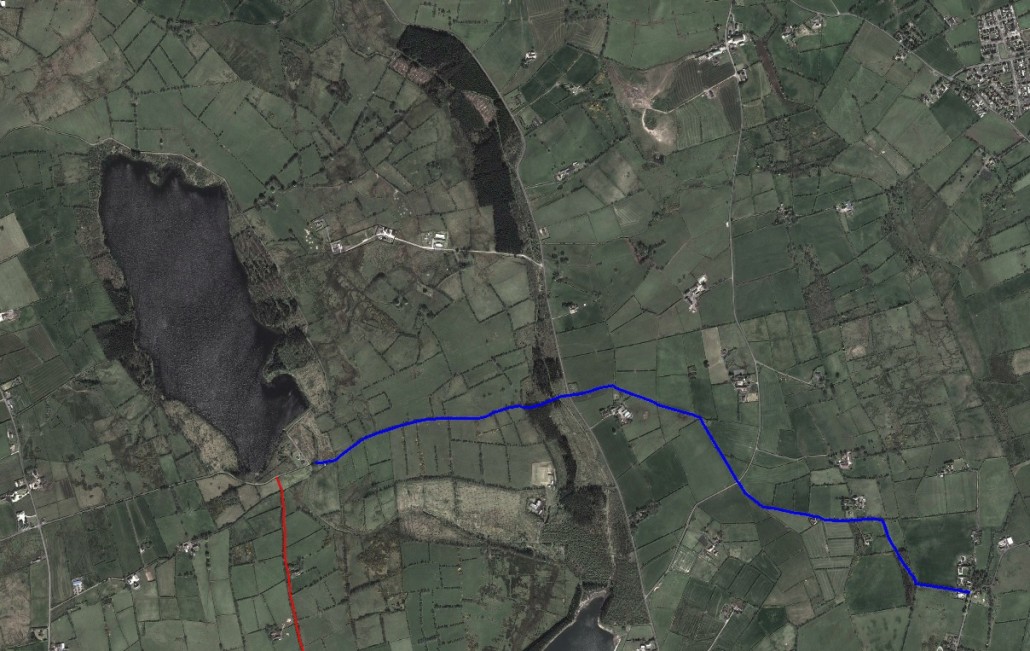

The Cassie Today

Lough Mourne was converted into a water reservoir in the 1930s. Coniferous trees were planted surrounding the Lough to prevent “farming pollution” from the surrounding area. It was probably around this time that Lough Road was properly paved, providing access to Lough Mourne from the town, via Red Brae Road. To the east of the reservoir, a gravel trail winds up around east of the Lough and ends at Loughmourne Road in the far north-west. The Lough is also accessible via Harts Loanen.

To the south-east, the lane soon becomes completely wild again, as the remaining section of the Cassie begins. It follows a rocky and steep path down towards Beltoy Road. After crossing the road, the Cassie continues to wind through farmland to the east. The trail turns further south at the “Resting Slap” – a ‘slap’ being Ulster Scots for a gap in the hedgerow, allowing from cattle to pass through.

After this feature comes a fairly interesting spot – the site of the Witchthorn. In folklore witch-thorns were thought to house fairies, or be trees around which witches would dwell. Such trees survived for so long simply because people would be too frightened to remove it or cut its branches. It is for this reason that it is fairly surprising that there is no sign of the tree today. Alexander Johns drew a picture of the tree in about 1860, so it was likely removed around the turn of the century – could the tree have left behind a curse on the Cassie?..

The Witchthorn gave its name to the Witchthorn National School, which was built just next to it. This building is also unfortunately gone, but the space where it once stood is very apparent.

Further south-east the trail comes to a junction with a private trail leading onto farmland at Porg Hill. This hill has quite possibly the most wide-reaching view of any hill on the northern shore of Belfast Lough, save perhaps the summit of Cave Hill in Belfast. Belfast and Carrickfergus can be clearly seen, as can the coast of Scotland as far north as the Mull of Kintyre. On the summit, an ancient fort once stood, and the foundations can be faintly made out.

Ignoring this junction, the Cassie turns east again onto a much better surfaced section – a necessity for accessing the few remaining homes and farms still in existence along the trail. A farm some of the way down this stretch hides an offshoot of the trail, which made a beeline north, eventually connecting the Cassie to the Jackson homestead, where the parents of future US President Andrew Jackson once lived on their family farm, and where Jacksons still farmed for many years to come. The house is in ruin today.

The trail becomes wild again for its final stretch, which eventually ends on Dalways Bawn Road. The trail beyond this point, like the section west of Lough Mourne, disappears under modern fields and farms. A short walk south on the road leads the traveller to Dalways Bawn itself, and onwards to Dobbsland.

Bibliography

- Much information on the cattle trail came from the blog of local historian Philip Robinson. His blog provides an extensive and in-depth tour of the Cassie in much greater detail.