Welcome to Carrickfergus History

Carrickfergus – or simply ‘Carrick‘ – is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It is located 11 miles north-east of the Northern Irish capital of Belfast, and has a population of some 27,000+ people. It is located within the Mid and East Antrim Borough Council area – which was formed in 2015 from the merging of Carrickfergus, Larne and Ballymena borough councils – and is part of the Belfast Metropolitan Area, or “Greater Belfast”. The town is twinned with the US cities of Portsmouth NH, Jackson MI, Anderson SC and Danville KY, as well as the Polish city of Ruda Śląska. It is the oldest town in County Antrim and one of the oldest in Northern Ireland.

Etymology

The area which is now Carrickfergus, or perhaps just the rock that the castle sits upon, was alleged to have originally been known as Dunsobarky or Dun-Sobairchia (translates roughly as “strong rock” – Dun signifying an insulated rock and Sobarky meaning “powerful” or “strong”). The application of this name to Carrickfergus was first recorded by 18th century historian Charles O’Conor in his map of Ireland, however it has been suggested that O’Conor made an error in attributing the name to Carrickfergus when it was in fact supposed to be applied to Dunseverick (Dún Sobhairce), a hamlet on the north coast.

In popular legend, Carrickfergus claims its roots back to the late 5th and early 6th centuries CE, and its alleged namesake King Fergus Mór mac Eirc, an Irish king of Dál Riata. The story is often told that Fergus left Ulster around this time to forge a kingdom in Scotland. He is said to have returned to Ulster in search of an ancient healing well to cure his leprosy – this well could be the one which still exists underneath the castle keep or possibly what would become St Brigit’s (St Bride’s) Well which is located north of the town centre. The well was quite familiar to pilgrims and would undoubtedly have been connected to monastic activity in the area during the 10th and 11th centuries, about which very little is known. During a heavy storm, it is said that Fergus’s ship was wrecked on a volcanic dyke by the lough shore, which became loosely known as “Carraig Fhearghais” – the Rock of Fergus – providing the area with a new name. The king’s body is said to have washed ashore and been buried somewhere in nearby Monkstown by the monks.

Though even local tourist information reflects this myth almost as fact, there is no evidence that any such event ever occurred.

Fhearghais or Fairge?

As above, it is widely accepted that the name Carrickfergus comes from the legend of Fergus and his ill-fated voyage. However, J Bell wrote in A Conjecture as to the Origin of the Name of Carrickfergus that the name is more likely to have come from the Irish Carraig na Fairge, meaning “Rock of the Sea”. He did unfortunately come to this conclusion through mistaking Fergus Mór mac Eirc with the fictional King Fergus I, and so dismissed the accepted story. His point on the Irish name however remains valid, and he points out similar historical names as far afield as County Clare in the Republic of Ireland, such as Fortfergus, the River Fergus and Knockfergus (from the Irish Cnoc na Fairge, meaning “hill of the sea” or “rock of the sea”). Carrick itself was known as Knockfergus during the Elizabethan era.

This is likely the true origin of the name “Carrickfergus”.

Variations

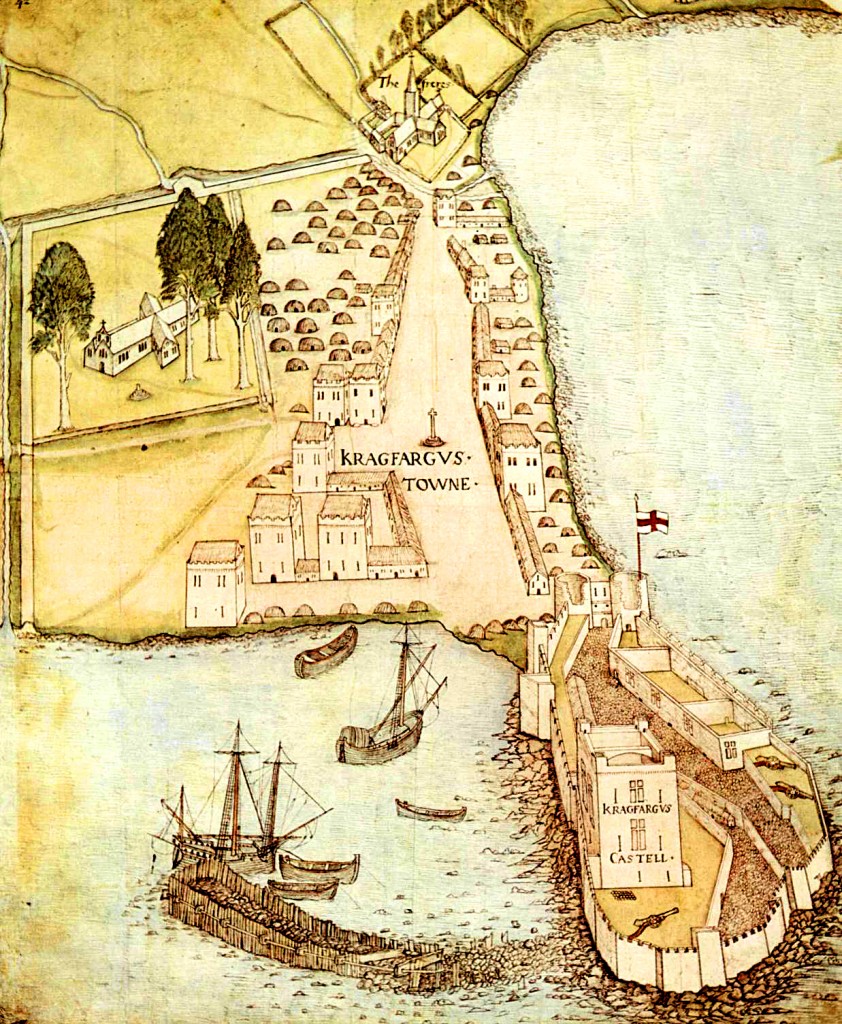

The town was first referred to as “Cragfergus” or “Carrigfergus” by the time written works and maps began to be produced, and later “Kairrigfergus”, “Kragfergus”, “Kragfargus” or “Carraigfergus”, although the Irish-derived “Carraigfergus” has now taken prominence. The first two spellings are most likely of Welsh origin, a result of the amount of English knights and soldiers of Welsh descent, mostly archers travelling with John de Courcy’s army, who came to Ireland at around this time under the authority of King Henry II, and inspired the naming of conquered lands under the Welsh language. During the reign of Elizabeth I, the town was normally referred to as “Cragfergus” or “Knockfergus”.

History of Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus far predates the Northern Irish capital of Belfast. It was in existence hundreds of years before the future capital city, was larger and more strategically and economically important than Belfast, and even comprised its own county. Belfast Lough itself was known as “Carrickfergus Bay” until well into the 17th century, after which Belfast overtook the town as the prominent power and regional capital.

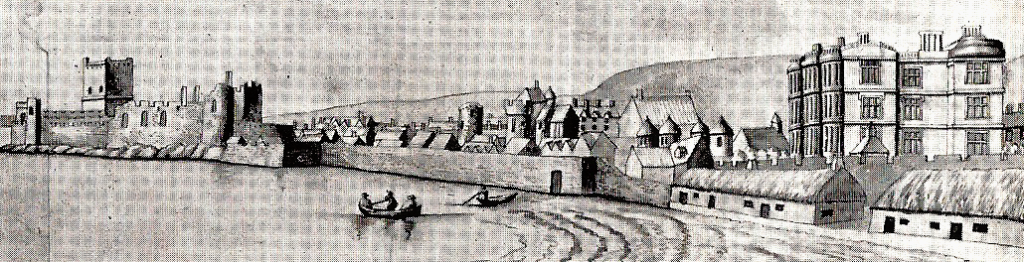

As a historical walled town, Carrickfergus originally occupied an area of approximately 100,000 square metres, which now comprises the bulk of the town centre. The wall is still standing in many places, and in various states of preservation – the best example of which is the North-East Bastion at Joymount.

Pre-1177

Not much is known about the area that would become Carrickfergus prior to the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland. There are multiple sites in the area where evidence of prehistoric settlements have been uncovered, most notably at Lough Mourne just north of the present-day town. An old story tells of a hag who travelled through the area and was refused the hospitality of the inhabitants of a village settlement here. She cursed the town to a watery fate, and the village was flooded forever. Legends aside, a number of crannogs were uncovered during draining of the lough in 1881, as well as several ancient structures and a wooden canoe – all thought to be late-Neolithic in origin.

Monastic activity is very sparsely documented in the area, although mostly further afield in the Monkstown area. Kilroot, just east of Carrickfergus is frequently noted as having been founded as a monastic and ecclesiastical site in around 412CE, although we believe this date to be closer to 500CE based on our own research. Kilroot is thought to have operated with both a bishop and abbot during the Early Christian period, before being amalgamated into the diocese of Connor some time before the year 1100. It is possibly the oldest documented settlement in the area.

The Anglo-Norman Era

Carrick’s history as an inhabited town began during the Norman invasion of Ulster in around 1177, when Anglo-Norman knight John de Courcy arrived in the area after invading Ulster with his army, in an attempt to gain his own Earldom.

In January 1177, and without King Henry II’s leave, he marched north from Dublin with 22 knights and 300 foot-soldiers and horsemen, launching a surprise attack on Dún Dá Leathghlas (now called Downpatrick) and moving on until reaching Coleraine. He went on to conquer most of eastern Ulster, which was controlled by the ancient Irish kings, in the following months before finally settling in the area now known as Carrickfergus. His progress was swift, due to the far superior weaponry used by the Norman soldiers. He established his headquarters in Carrickfergus and had begun construction of Carrickfergus Castle on top of the ‘rock of Fergus’ by the beginning of 1178, using stone ferried across Carrickfergus Bay from Cultra – this fine stonework can still be observed in the corners of the Great Keep. The establishment of St Nicholas’ Church followed in around 1182.

de Courcy is also credited with the founding of the St Mary’s Premonstratensian Abbey in Woodburn (Woodburne Abbey), to which the parish of St Nicholas was granted. St Nicholas’ own website queries whether the church was granted to the Woodburn Abbey of the White Canons or the later Friary of the Franciscan monks located in the town proper. Despite St Nicholas’ own doubts, it is clear that the church was affiliated with Woodburn.

de Courcy began to mint his own coinage in Carrickfergus and Downpatrick. This was interpreted as an act of a sovereign ruler by King John of England, who believed de Courcy was forging a petty kingdom, and so in 1199 John dispatched the knight Hugh de Lacy to wage war on de Courcy. He captured de Courcy in 1204 and expelled him from Ulster. The account of his capture appears in the Book of Howth, and verifies de Courcy’s reputation as an incredibly powerful and god-fearing warrior:

Sir Hugh de Lacy was commanded to do what he might to apprehend and take Sir John de Courcy, and so devised and conferred with certain of Sir John’s own men, how this might be done; and they said it were not possible to take him, since he lived ever in his armour, unless it were a Good Friday and they told that his custom was that on that day he would wear no shield, harness nor weapon, but would be in the church, kneeling at his prayers, after he had gone about the church five times bare-footed. And so they came at him upon the sudden, and he had no shift to make but with the cross pole, and defended him until it was broken and slew thirteen of them before he was taken.

In May 1205, following de Courcy’s expulsion, King John created de Lacy the 1st Earl of Ulster, and Carrickfergus became the seat of the Earldom.

de Courcy returned in July 1205 with a force of Norse soldiers and ships on loan from his brother-in-law Rögnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of Mann. They landed at Strangford and proceeded to besiege Dundrum Castle, which de Courcy himself had built. Ironically, de Courcy’s siege failed, as the defences that he himself had built were simply too strong. He was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London on the orders of King John, and his lands and titles were revoked.

A legend exists that de Courcy, after having been imprisoned for some time, begrudgingly accepted King John’s request for him to act as his champion in a tourney against a champion of Philip Augustus, King of France. After the French champion fled rather than face the former knight, de Courcy in a show of strength cleft a metal helmet in half with his sword, embedding the sword so deep in the wood beneath it that only he alone could remove it. The legend is disputed by many, but there is a significant amount of reliable references that at least partially authenticate the story.

Most historical accounts show that lived most of the rest of his life incarcerated and in poverty, before being released after swearing to dedicate the remainder of his years to a personal pilgrimage to the Holy Land. de Courcy allegedly died in obscurity near Craigavon in around 1219. His armour is still displayed in the Tower of London.

de Lacy was relieved of command in 1210, when King John himself arrived and placed the castle under royal authority after a 9 day siege. John is thought to be the only English or British monarch to have stayed at the castle for any notable length of time, staying in the castle for ten days in July 1210. Under John’s authority, the castle was further fortified by adding an exterior curtain wall – creating the middle ward of the castle – on the landward side, a task overseen by one of John’s appointed constables De Serlane.

de Lacy crusaded in France for some years after his expulsion, but returned in 1224 and attempted to siege Carrickfergus unsuccessfully. He eventually regained his Earldom in 1227, despite his attack on the town, when King Henry III allowed him to return. He founded the Franciscan Friary in 1232, which stood where the modern Town Hall and Carrickfergus Library now stand. He also oversaw the final construction of the castle, including the outer ward, gatehouse and gate towers. de Lacy married Emmeline de Riddlesford in around 1242 and died childless sometime after the 26th of December 1242 according to most accounts, leaving the Earldom of Ulster to become extinct and revert to the crown. His remains were eventually interred at the Friary in 1443 – it unknown whether his remains were moved when the friary was demolished. The huge extensions and additions to the castle, which de Lacy began, were finally completed in 1250.

The Scottish Venture

On the 26th of May 1315 Edward Bruce, the younger brother of King of Scotland Robert the Bruce, landed over 6000 men just north of Larne. Ireland had not had a High King since Ruaidhrí Ua Conchobhair was deposed at the beginning of the Norman Invasion. Edward, who boasted a lengthy royal Irish ancestry, sought to become High King of Ireland with the intention that Ireland could be used as a second front in the ongoing war with the English, expelling the Anglo-Normans from Ireland in the process.

Bruce’s forces moved down the coast, fighting the forces of the Earl of Ulster, before capturing and burning Carrickfergus. They were however unable to take the castle, and so began a lengthy and bitter siege. Shortly afterwards in the town, King of Tír Eóghain, Domhnall mac Briain Ó Néill met up with the Scots and swore fealty to Bruce and proclaimed him High King, however this proclamation was largely ignored by the more powerful Kings of Ireland. Bruce left Carrickfergus in late June, leaving behind a considerable force to continue the siege. An attempt to replenish supplies from the sea by Sir Thomas de Mandeville in Easter 1316, resulted in his defeat and death. It was reported in the Laud Annals that of 30 Scots taken hostage during a parlay, 8 were killed and eaten, as the castle’s inhabitants became desperate for food. The castle surrendered in September 1316.

Bruce was defeated and killed by the forces of Sir John de Bermingham in 1318, after which the castle and town came back under the control of the crown (and at this point King Edward II).

The Irish Era

On the 6th of June 1333 the 3rd Earl of Ulster William de Burgh was murdered, leaving only his infant daughter as heir, effectively collapsing the Earldom. All subsequent Earls would remain absent from the town and rule from afar, but the castle remained both under the control of the crown and the principle administrative centre in the north of Ireland.

With the weakening of the Earldom the Clandeboye O’Neill clan, the ruling dynasty in most of western Ulster, took the opportunity to push eastwards from Lough Neagh until the English-controlled county of Carrickfergus was reduced to an area of around 5 square miles. Niall O’Neill burned Carrickfergus to the ground in 1384. After the O’Neills arrived in Carrickfergus, William de Burgh’s family seized his land, joined with the Irish and assumed Irish names and identities.

By this time the Highland Scots were settling in the northern parts of Antrim and, much like the Irish, were expanding into Anglo-Norman lands. Carrickfergus was raided and burned by the Scots in 1386 and again in 1402.

Although by 1400 most of eastern Ulster was firmly under the control of the O’Neills, a mutually advantageous arrangement existed between the crown and the Irish clans to keep the town and county of Carrickfergus under the effective control of the English. The English paid a “black rent” to the O’Neills, and as a result the town continued to be used as the primary sea-port in Ulster and a centre for huge amounts of local and international sea trade. This continued at least for the first part of the 1400s.

The Earldom of Ulster was detached from Ireland and merged into the crown in 1461 with the accession of Edward IV to the throne of England.

The town was put to the torch several more times in the following 150 years. In 1513 the Earl of Arran burned the town against the instructions of his king and in 1555 the Scots sieged the castle and burned the town once again. In 1573 the town was set ablaze again, this time by the Irish.

The castle was repaired and renovated in the mid 1500s, most notably to adapt the walls for cannon. It was at this time being used as a base for expeditions against the Scots for much of the mid to late 1500s.

The English Colonial Era

In July 1573 Walter Devereux, Earl of Essex set sail for Ireland with an army of around 1200 men and a number of knights and gentlemen, operating under the rank of Governor of the Province of Ulster. His intent was to establish an English colony in Ulster, which was at this time controlled entirely by the O’Neills and Somhairle Buidhe Mac Domhnaill (aka Sorley Boy MacDonnell). Although his endeavour was cut short on the orders of Elizabeth I, he brought with him several people of local importance such as John Dalway, who would go on to serve as Carrickfergus mayor twice and later establish a “cattle empire” in the area.

In 1595, at the beginning of the Nine Years War, the Irish clans under Hugh O’Neill rose into rebellion. They controlled the central part of Ulster, while the MacDonnells controlled the surrounding areas. The MacDonnells flirted with the idea of siding fully with the English to crush the rebellion, an aspiration they had in common.

In 1597, recently appointed governor of Carrickfergus Castle, John Chichester, began negotiations with one of Sorley Boy’s nephews James MacSorley MacDonnell over a period of raids and counter-raids between the Scots and the English. It was later on this year that the Battle of Carrickfergus took place in the hills between Carrickfergus and Larne. Chichester and MacDonnell had agreed to parley over a number of grievances raised by the Scots over military operations carried out in and around Scottish territories. James arrived around four miles outside Carrickfergus on the agreed date of the 4th of November 1597, accompanied by some 1300 troops and 500 musketeers. Chichester rode out to meet them, at the head of just five companies of foot and one company of horse. Chichester halted his troops shortly before meeting the Scots and discussed with his officers the possibility of breaking the parley in favour of battle. A senior officer urged Chichester to continue with the parley, knowing that the troops were fatigued from a recent expedition. Chichester asked his commander, Captain Merriman:

Now, Captain, yonder be your old friends. What say you? Shall we charge them?

Merriman and the commander of the cavalry, Moses Hill, agreed with Chichester’s suggestion and the troops engaged the Scots in battle – and so began the Battle of Pin Well, fought in Aldfracken Glen near modern-day Ballycarry. At first the Scots faltered, being forced from hill to hill, but spotting a flaw in Chichester’s charging formations they eventually overcame the English troops, even after a small reserve force arrived from Carrickfergus to prevent a complete massacre. Chichester was shot cleanly through the head and died immediately. Out of a force of no more than 350 men, 180 were killed and a further 30-40 troops injured, with some men swimming across Larne Lough to escape the battle, ending up in Islandmagee. MacDonnell’s losses were comparatively few. After the battle, it was recorded that MacDonnell was disappointed in Chichester’s “bad intentioun”, when the Scots never intended to fight and were in gentle spirit on the day. Chichester’s head was allegedly cut off and used as a football by the MacDonnell troops.

In late 1598 or early 1599, Chichester’s younger brother Sir Arthur Chichester was appointed governor of the town in his brother’s place. He quickly became a hate figure among the Irish clans for his aggressive methods, including a “scorched earth” policy of destroying anything of use to the enemy when passing through or leaving an area. He surrounded O’Neill lands with strong garrisons in order to starve the Irish, a tactic he carried out ruthlessly. Other than commanding troops in Ulster, Sir Arthur was also responsible for the plantation of English and Scottish peoples in Carrickfergus.

Despite moving on to become Lord Deputy of Ireland on the 3rd of February 1605, Chichester oversaw the building of Carrickfergus town wall from 1608 until its completion in 1618.

The Nine Years War ended in 1603, with the signing of the Treaty of Mellifont between the Crown and the Irish. The MacDonnells ended their campaign as a result of the ascension of the Scottish King James to the English throne.

In 1610, Sir Arthur Chichester commissioned the building of a vast Jacobean mansion, which was named “Joymount Palace”, or sometimes simply “Joymount”, after the previous Lord Deputy of Ireland Lord Mountjoy. It was designed by English architect Inigo Jones. Chichester retired to the mansion after being forced to relinquish his term of office due to ill health in February 1616, and spent most of the rest of his life in Carrickfergus.

He died in London in 1625 and was buried in St Nicholas Church in the town some months later. His mansion, which occupied the land where the modern-day Town Hall and library stand, was unfortunately destroyed by fire in the early 1700s. One of the four corner towers still partially survives, built into the back of the Town Hall.

During the early 1600s, the castle was updated to support artillery, including further modification for cannon. The circular towers were reduced to half their original height and each modified into their current semi-circular shape.

In 1637 the town’s customs rights, which ran from Groomsport in County Down to Larne in County Antrim, were sold to Belfast. This was primary factor for the decline of Carrickfergus as an important seaport in Ulster, in favour of the future capital city. It was also sometime in the 1600s that Carrickfergus Bay started to assume the name ‘Belfast Lough’, which it is still known as today.

From 1638 to 1640, during the Bishops’ Wars, King Charles I commissioned a secret army to be raised, which was to be used to put down the rebellion in Scotland. Irish Catholic gentry slowly recruited and mobilised the army in Carrickfergus, in return for concession of Irish Catholics’ longstanding requests for religious tolerance and land security.

In 1641 the town acted as a refuge for protestants fleeing the Irish Rebellion. It in turn acted as a base for a notorious counter-attack and massacre of Catholics in Islandmagee. Scottish General Robert Munro arrived in Ireland the same year to put down the Irish rebels and protect the protestant settlers. He captured Carrickfergus Castle, holding the town for the Scots, before moving on to capture Belfast. The developing civil war in England was confusing the military situation in Ireland, and the castle changed hands several times. Most notably in 1647, George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle laid siege to the castle. In September 1648, a large section of Munro’s men betrayed him, and so the castle was delivered to Monck, who had Munro arrested and sent to the Tower of London, where he remained for some five years.

In the 1650s and 1660s, the town began to expand beyond the walls. A western suburb became known as the Irish Quarter and the eastern suburb, founded around 1665 by Scottish fishermen who fled persecution in Argyle and Galloway, became known as Scotch Quarter. The names of these suburbs are reflected in several modern day street names in Carrickfergus, and the locations of the suburbs are still apparent.

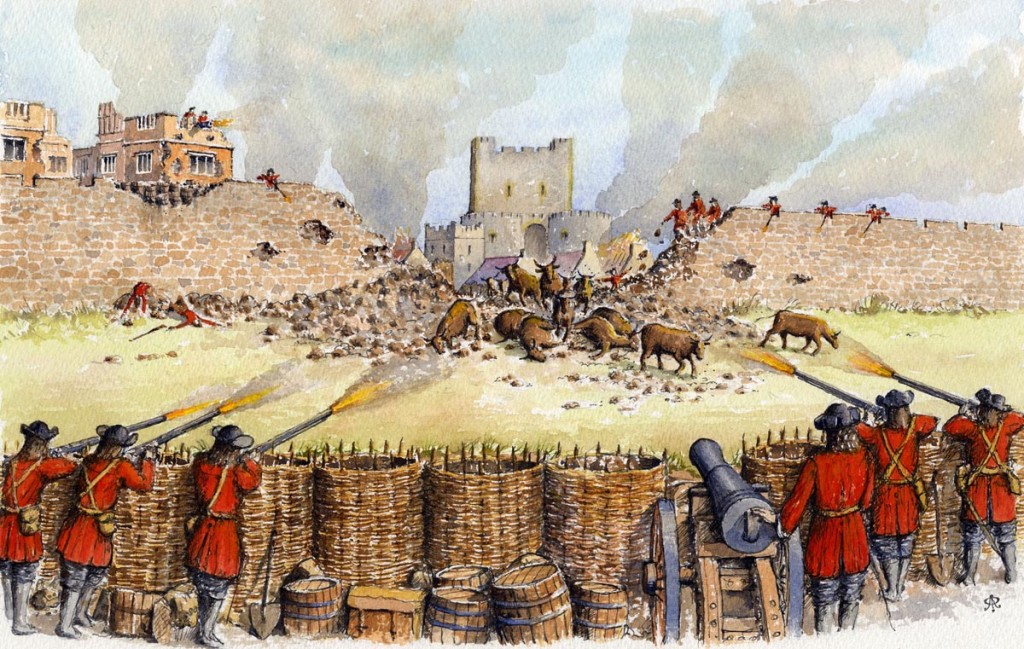

In 1688, despite the local peoples’ sympathies for the Williamite cause, the castle and town were captured and held by the Jacobite forces of James II, as he fled to Ireland in an attempt to hold the crown. In 1689 Frederick, 1st Duke of Schomberg landed at Groomsport with a Williamite army and on the 20th of August laid siege to the castle with mortar fire, capturing it seven days later before sweeping steadily south.

At 3.30PM on the 14th of June 1690, William of Orange landed at the Old Quay at Carrickfergus Castle, at the head of the remainder of the Williamite army. The castle garrison formed a guard of honour as the townspeople applauded his arrival. A chosen spokesperson welcomed William by saying:

William, thou art welcome to thy Kingdom

to which the King replied:

You are the best bred gentleman I have met since I came to England.

With this, he mounted his horse and began his journey towards Belfast and Lisburn, eventually ending at the Boyne, where he defeated James II in the Battle of the Boyne.

The town was the scene of the last witchcraft trial in Ireland in 1711. Eight women were charged with offences including tormenting the victim, Mary Dunbar, causing her to experience fits or seizures and finally causing her to vomit materials such as feathers and yarn. It was also documented that three strong men could scarcely hold her down and that she was often pulled out of bed by an invisible force. Despite Judge Upton’s opinion that they should be acquitted, the jury found them guilty and they were sentenced to twelve months imprisonment and four sessions in the pillory in Carrickfergus town centre.

During the Seven Years’ War, in February 1760, Admiral Francois Thurot of the French Navy was carrying out smuggling and privateering activities around the Mull of Galloway and in the North Channel. Buffeted by bad weather and with his ships in need of provisions, Thurot landed his 44-gun frigate and two sloops of war at Kilroot Point to the east of Carrickfergus, and proceeded to attack the town with upwards of 800-1000 men. The garrison put up admirable defence, but were forced to surrender after running out of ammunition. Thurot left Carrickfergus some days later after replenishing his ships. It is recorded in the Masonic Grand Lodge records that the warrant and jewels of Carrick’s Lodge 270 were confiscated by Thurot, who was himself a freemason. They were quickly returned by the Royal Navy’s Captain Elliot, after Thurot’s fleet was defeated just off the Isle of Man.

Andrew and Elizabeth Jackson, parents of future US President Andrew Jackson, lived at their homestead north-east of the town, in the Bellahill townland close to Ballycarry. They relocated to a thatched cottage in Boneybefore a couple of years before emigrating to South Carolina in 1765. The ruins of the house still remain at the Bellahill site and Jackson descendants allegedly farmed in the area until well into the 20th century. A local story recalls that Andrew Jackson was in fact born in Boneybefore and smuggled into America under his mother’s dress, therefore making his Presidency illegitimate – there is even evidence of him being born in Boneybefore before embarking on the voyage to America.

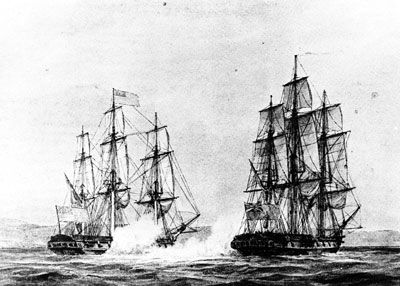

In April 1778, during the American Revolutionary War, John Paul Jones commanding the American ship the USS Ranger, attempted to capture a Royal Navy ship HMS Drake, which was moored at Carrickfergus. Not wanting to sail too close to the formidable castle, he lured Drake away from its mooring, after which the two sloops-of-war battled on the 13th of April in the North Channel, where he dealt a crushing defeat to the Royal Navy ship, capturing it and its crew. The Ranger would be captured by the Royal Navy two years later and re-commissioned as the HMS Halifax.

From 1797, the castle was used as a prison and was heavily guarded during the Napoleonic Wars, to protect against attack by the French.

The 1790s also saw considerable support in Carrickfergus for the United Irishmen and similar movements. In 1797 William Orr was charged in Carrickfergus Courthouse (which is now the Town Hall) with administering the oath of the United Irishmen to two soldiers and hanged at Gallows Green just outside the town on the 14th of October. Similarly, United Irishmen founder Henry Joy McCracken was captured in 1798 in the outskirts of the town, while trying to escape to America during the Irish Rebellion. He was sent to Belfast where he was tried, and hanged in Cornmarket on 17th July 1798.

The Modern Era

Due to Carrick’s loss of importance as a commercial centre, the town turned to newer industries in the 1800s.

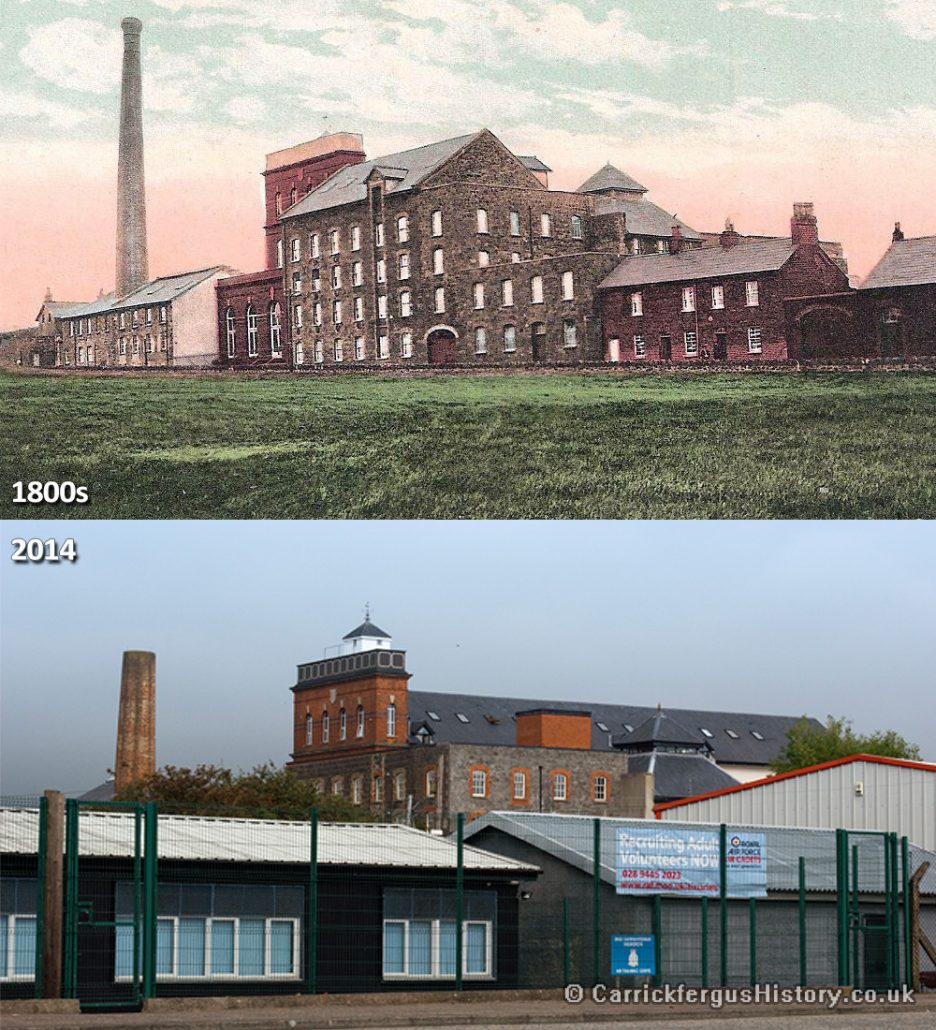

An 1832 Ordinance Survey map shows a “cotton manufactory” on what is now Taylor’s Avenue, which may date back to around 1790. It was replaced in 1839-1840 by the Barn Mills, constructed by James Cowan who owned the previous factory and the nearby Barn Cottage (also known simply as “The Barn”), which was itself built in around 1790. The new complex was specialised for flax-spinning, using techniques pioneered by the Mulhollands of Belfast. It was acquired by James Taylor in 1852, who continued to invest in the flax industry in the area. He extended the mill eastwards in 1870, doubling its size, and again in around 1900.

In the 1840s the county of Carrickfergus was dissolved and Carrickfergus town became a part of County Antrim, where it remained until 2015. As a result, the court and gaol were relocated to Belfast (the latter to Crumlin Road).

In 1845 Carrick also became a shipbuilding town, with the launch of the brigantine David Legg. In 1861, Paul Rodgers became foreman of the shipyard, and designed the ship Dorothea Wright, amongst others. The most notable ship designed by Rodgers and built in 1893 is the Result, a Topsail Schooner which now resides in the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum in Cultra.

In 1848, the town was connected to Belfast by railway via the Belfast and Ballymena Railway line. Later in 1862, the Carrickfergus and Larne Railway opened, along with Carrickfergus Railway Station.

The Carrickfergus Gas Company was formed in 1854 and quickly acquired premises for the Gasworks in the Irish Quarter. The first gas lights were lit on the 17th of September 1855.

On the 2nd of April 1912 the residents of Carrickfergus turned out in their thousands to watch as the RMS Titanic made its first ever journey up the lough from its construction dock in Belfast. The famous passenger liner was anchored overnight just off the coast of Carrickfergus, before continuing on its all-fated journey.

During World War II, Northern Ireland was an important military base for United States Naval and Air Operations and a training ground for American G.I.s. The First Battalions of the elite US Army Rangers were founded, activated and based in Sunnylands Camp, Carrickfergus for their initial training on 19th of June 1942 under the command of Major William Darby. The US Rangers Centre in nearby Boneybefore pays homage to this period in history.

It is known that prisoners-of-war were imprisoned in Carrickfergus during World War II. Documentary evidence exists of Italian soldiers were imprisioned and put to work at Sullatober Mill, where both American and Belgian forces were based. Although little – if any – acknowledgement exists, many locals recall trading cigarettes and other goods with German prisoners held in Nissen huts in the American-run Sunnylands Camp. The reports are certainly viable, as Sunnylands Camp was home to the commando training ground for the newly formed US Army Rangers. A memorial archway exists in Prospect (on Woodburn Road) to honour the Belgian troops who trained in the area dring the war.

Carrickfergus and the surrounding area is also home to numerous civil-defence and anti-aircraft positions, many of which were put in place in the first few years of the 20th century. A documented case of anti-aircraft batteries seeing combat action is that of the battery gun on Neills Lane in Greenisland, which opened fire on a Luftwaffe aircraft as it flew up Belfast Lough during the Belfast Blitz in 1941. The gun failed to hit its target, and only suceeded in breaking a number of windows in the village. As it became clear that a full-scale air attack on Belfast was taking place, residents took cover in the air-raid shelters, the only time they are known to have been used.

Barn Mills on Taylors Avenue was converted to manufacture parachutes during World War II and was purchased by the wool-spinning firm of Jeremiah Ambler in 1945, after the Northern Ireland government put forward a grant to try and boost post-war employment numbers. At its post-war height, it employed over 500 people. The mill persevered through the introduction of mass manufacture of synthetic fibres and spun wool cloth and mohair until about 2002, when Ambler’s ceased operations. The mill was extensively renovated and converted into apartments in 2006.

In 2019 the Great Tower of Carrickfergus Castle had its aging roof replaced. The roof dated to the early 20th century, when it replaced brick vaults installed on the roof in the 1800s, and was in disrepair. Twin gable roofs were installed, made from green oaks downed in County Wicklow by Storm Ophelia in 2017, and assembled using timber pegs and traditional medieaval techniques where possible. During construction, stones were removed from the walls of the Great Tower which may have been some of the earliest used in the castle’s construction. One of these stones exhibited what may be a masons mark. During the replacement of the roof, an archaealogical survey of the tower was carried out which revealed a stepped doorway or passage hidden within the wall of the spiral staircase, and uncovered the bricked-up windows of the now lost 4th floor of the keep. The Victorian tunnel, which leads from the harbour-side into the inner ward of the castle, was uncovered and used to move materials into the castle, and the external iron doors have now been replaced with gates, providing a view into the inner ward from outside.

International Relationships

Carrickfergus’ official international relationships, including Twin Towns and Sister Cities:

- Portsmouth, New Hampshire, United States [Since 1994]

- Jackson, Michigan, United States [Since 2006]

- Ruda Śląska, Poland [Since 2008]

- Anderson, South Carolina, United States [Since 2008]

- Danville, Kentucky, United States [Since 2009]

Selected Bibliography and Sources

- Cyril Falls. Elizabeth’s Irish Wars. 1997.

- Samuel Lewis. A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. 1837.

- A Short History of Royal Arch Masonry in the Towne of Carrickfergus

- Steinbeck’s Redemption

- Old Carrickfergus Postcards

- Title image from marinas.com

If you spot any mistakes or irregularities, please contact us or leave a message on Facebook.

Revision 3a, May 2022.